Meet our crack team of C&C Wales advisors. This photo was taken after our workshop at Swansea University Department of Classics. Over a heady mix of chips, coffee and sandwiches, we talked about avenues of research for the Welsh limb of our C&C project. From the excellent Swansea Classics and History Department we had Ceri Davies, Mark Humphries, Evelien Bracke, Christopher Stray and Gethin Matthews; from the South Wales Miners’ Library – Sian Williams; Janett Morgan travelled from Cardiff, and Chris Pelling and Mai Musie came from Oxford. Edith and I were bowled over by the sheer quantity and energy of classics among the working class of Wales in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The exceptional ‘rags to riches’ (or at least ‘rags to Romans’) stories of the likes of Joseph Wright, Richard Porson and other English and Scottish autodidacts appear to be less exceptional (i.e. more common) in Wales. As Gethin Matthews and Ceri Davies explained, the publication of a somewhat damning inquiry into the educational status of Wales in 1847 marked an educational – and therefore classical – watershed. Inextricably linked with contemporary political protest, which sprang from the exploitation of Welsh workers (think, the Merthyr Rising, 1831, and the Rebecca Riots, 1839-43), a movement to educate the Welsh rural poor was set in motion. Prof. Davies paraphrased the dominant message of report succinctly in his essay on Classics and Welsh Identity: “The Welsh needed civilising.”

The exceptional ‘rags to riches’ (or at least ‘rags to Romans’) stories of the likes of Joseph Wright, Richard Porson and other English and Scottish autodidacts appear to be less exceptional (i.e. more common) in Wales. As Gethin Matthews and Ceri Davies explained, the publication of a somewhat damning inquiry into the educational status of Wales in 1847 marked an educational – and therefore classical – watershed. Inextricably linked with contemporary political protest, which sprang from the exploitation of Welsh workers (think, the Merthyr Rising, 1831, and the Rebecca Riots, 1839-43), a movement to educate the Welsh rural poor was set in motion. Prof. Davies paraphrased the dominant message of report succinctly in his essay on Classics and Welsh Identity: “The Welsh needed civilising.”

A need for home grown Methodist clergymen also gave rise to various important training establishments, including a number of non-conformist schools and dissenting academies. These schools provided a route from the long impoverished Welsh valleys to academic excellence and encounters with classical texts and tales. The classical encounter of Robert Roberts – ‘Y Sgolor Mawr’ (‘The Great Scholar’) is a good example. Roberts was taught Greek and Latin in Bala (Gwynedd) by Calvinist Methodists, and later in life – when he was applying to become a deacon – was tested by the Bishop of St. Asaph on his sight-reading of Greek. You can read more about Roberts in the C&C encounter archive.

As Gwyneth Lewis (former poet laureate of Wales) told us on Tuesday, the nineteenth century experience of classical literature was driven in large part by the educational impulse to have Welsh clerics who could access directly the Biblical texts – written in Greek, Latin and Hebrew. From our early explorations in the archives, we have found that along this righteous path to clerical excellence many students of the Lord’s work strayed and, indeed, stuck fast on the many vibrant pagan classical texts.

As Gwyneth Lewis (former poet laureate of Wales) told us on Tuesday, the nineteenth century experience of classical literature was driven in large part by the educational impulse to have Welsh clerics who could access directly the Biblical texts – written in Greek, Latin and Hebrew. From our early explorations in the archives, we have found that along this righteous path to clerical excellence many students of the Lord’s work strayed and, indeed, stuck fast on the many vibrant pagan classical texts.

From such beginnings a rich tradition of classical scholarship built up in Wales, and excitingly one that was relatively free from the aristocratic trappings of the English ‘public school’ classical tradition. This tradition of religiously, politically and socially dissident classics in Wales perhaps reached its zenith in the appointment and subsequent teaching and research career of the Communist classicist Benjamin Farrington, who held the professorship of classics at Swansea University for twenty years, from 1936 to his retirement in 1956. Farrington is most widely known for his important and accessible books on Greek Science. It was brilliant to hear stories about Farrington still buzzing among current members of the Classics Faculty.

On Thursday I took the train from Swansea to Neath, where I met Hywel Rogers (pictured left). Hywel came to the Romans in the 1970s via the unlikely route forged by his passion for off-road motorcycling. He and his friends began to explore the Main Roman road that runs from Caerleon (Isca) to Carmarthen (Maridunum). Over the years as the friends rode further and further along the road, Hywel became more and more fascinated by all things Roman. When I asked him if he learned Latin at school he laughed; it appears Latin was for the grammar / county schoolboys across the way, not for those at the less ‘academic’ Neath Tech., which primarily prepared its pupils for lives in engineering and the local coal industry.

On Thursday I took the train from Swansea to Neath, where I met Hywel Rogers (pictured left). Hywel came to the Romans in the 1970s via the unlikely route forged by his passion for off-road motorcycling. He and his friends began to explore the Main Roman road that runs from Caerleon (Isca) to Carmarthen (Maridunum). Over the years as the friends rode further and further along the road, Hywel became more and more fascinated by all things Roman. When I asked him if he learned Latin at school he laughed; it appears Latin was for the grammar / county schoolboys across the way, not for those at the less ‘academic’ Neath Tech., which primarily prepared its pupils for lives in engineering and the local coal industry.

The way Hywel patiently teaches me about the Roman archaeology and history of the area reminds me how ridiculous it is that Latin has a history of being taught only to those pupils who have shown an early aptitude at passing tests, rather than an interest in what may be read in that language. It is, of course, a truism to say that classical culture is only elitist when provided only to an elite. It is encouraging that Latin is now taught in over 1,000 state schools in Britain. I just hope that it is not only being taught to those pupils who are by various means predisposed to academic and socio-economic success.

Hywel made his living as a ‘fitter of excavators’ (a.k.a. an assembler of big diggers). Now retired, he continues the valuable work of many former distinguished members of the Antiquarian Society of Neath, notably C. Stanley Thomas and William Chouls. Over the past twenty years or so, Hywel, who still often rides his bike up to the local Roman forts of Blaen-cwm-Bach and Coelbren has become fascinated by Roman Wales. His thirst for knowledge about these local landmarks, which if not studied (he warns) can become invisible to the communities that live among them, has taken him through the research folders of former antiquarians in the Neath Archives and led him to compile his own. With his help (fingers crossed) we will shortly add the classical encounters of his esteemed predecessors in the Neath Society of Antiquarians.

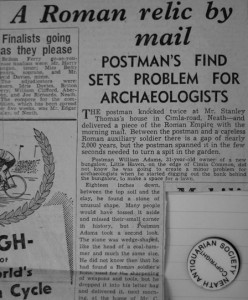

Both his school and the neighbouring county school stood directly on top of the Roman station known as Nidum. In 1949, when ground was being cleared for a new housing estate, the important Roman station fort was discovered by a team of amateur archaeologists, headed by former soldier, architect and surveyor, C. Stanley Thomson, and with the scholarly superintendence of Dr. V. E. Nash-Williams, of the National Museum of Wales. It was not only the working men who were employed in digging the trenches and sifting the earth of the site (pictured) who got to handle Roman artefacts in 1940s Neath.We have on record the story of William Adams, a postman in Neath, who discovered a Roman soldier’s hone (sharpening stone) in his garden when he was doing some gardening. Judging by the local press cuttings compiled by Thomson and stored in the archives, the excavation had a dramatic impact on the region, and the kindled interest was fanned further by free events such as a public lantern show and lectures given by Nash-Williams, among others, in the town hall.

Before leaving our friends in Swansea and Neath, Edith and I gave a paper called ‘Between the Party and the Ivory Tower: Classics and British Communism in the 1930s’, in which the Swansea-based Farrington played a leading role. Another chief protagonist of the tale of British Communist Classics was the Australian, Jack Lindsay. It stands as testament to the powerful, albeit somewhat supressed, legacy of the likes of Lindsay in the classical academy that two members of the Swansea faculty had books by Lindsay on their shelves. The fact that these books varied so extraordinarily from the cheap paperback edition of Lindsay’s translation of Petronius’ Satyricon (“The World’s Most Famous Erotic Novel”) owned by Prof. John Morgan (picture below) to Tracey Rihll’s copy of Lindsay’s more niche but no less fascinating monograph on Blast power and ballistics: concepts of force and energy in the ancient world, proves just how astonishingly deep, as well as broad, Lindsay’s classicism was.

Before leaving our friends in Swansea and Neath, Edith and I gave a paper called ‘Between the Party and the Ivory Tower: Classics and British Communism in the 1930s’, in which the Swansea-based Farrington played a leading role. Another chief protagonist of the tale of British Communist Classics was the Australian, Jack Lindsay. It stands as testament to the powerful, albeit somewhat supressed, legacy of the likes of Lindsay in the classical academy that two members of the Swansea faculty had books by Lindsay on their shelves. The fact that these books varied so extraordinarily from the cheap paperback edition of Lindsay’s translation of Petronius’ Satyricon (“The World’s Most Famous Erotic Novel”) owned by Prof. John Morgan (picture below) to Tracey Rihll’s copy of Lindsay’s more niche but no less fascinating monograph on Blast power and ballistics: concepts of force and energy in the ancient world, proves just how astonishingly deep, as well as broad, Lindsay’s classicism was.