Description

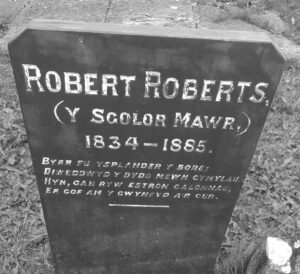

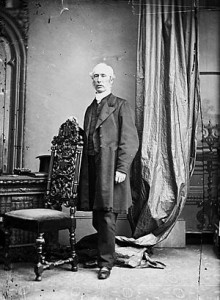

Meet Robert Roberts (1834-1903), known as ‘Y Sgolor Mawr‘ (the great scholar), who worked his way from extreme poverty and life as a farmer’s drudge to cleric and respected academic. Roberts, who – incidentally – was the cousin of the Welsh philosopher Henry Jones, grew up in Hafod Bach, on a tenanted farm in the hills of North Wales, which he considered neither pretty, nor sublime, but ‘ugly’ and ‘utterly uninteresting’. Too poor to afford schoolbooks, he struggled through Lewis Edwards’ Calvinistic Methodist College and, against all odds, excelled in his studies.

Meet Robert Roberts (1834-1903), known as ‘Y Sgolor Mawr‘ (the great scholar), who worked his way from extreme poverty and life as a farmer’s drudge to cleric and respected academic. Roberts, who – incidentally – was the cousin of the Welsh philosopher Henry Jones, grew up in Hafod Bach, on a tenanted farm in the hills of North Wales, which he considered neither pretty, nor sublime, but ‘ugly’ and ‘utterly uninteresting’. Too poor to afford schoolbooks, he struggled through Lewis Edwards’ Calvinistic Methodist College and, against all odds, excelled in his studies.

After just two years at school he spent a further two tutoring privately before heading to the teacher training college at Caernarvon. Soon after gaining teachers’ certificate from that college, Roberts bumped into an old childhood friend, Miss MacNamara, who was by this time a poor schoolmistress in Llanerchymedd. In a conversation reported by Roberts in his autobiography, Miss MacNamara likened her widowed landlady to Penelope:

MM: “She was like the woman in Homer, always with “suitors” dangling about her. However, they did not court me, and as they let me alone, I never troubled myself about them.”

RR: “And there was no Ulysses to pepper them, and no Minerva to help?”

MM: “Divil a bit did any Minerva show herself there, or anything belonging to her except the Minerva Press…”

Not long after qualifying Roberts grew tired of teaching:

“I’ve tried to earn my bread by teaching, but that bread is so bitter that it is uneatable.”

He longed to go to Oxford University to further his education, but his knowledge of Greek and Latin was insufficient for him to win a scholarship. Spurred on by stories of others who had made it to Oxford from the Welsh working class (notably Rev. Morris Williams), Roberts decided to gamble with the last of his savings and go for the entrance exams anyway:

“I had three months to read, and at it I went like killing snakes. I read up my Horace, Virgil, etc., and prepared to go up at the next October examination, coûte que coûte.”

He never did make it to Oxford. Instead in 1857 he enrolled at St. Bees Theological College, where he succeeded in beating his English public-school-educated contemporaries to the Greek Prize. His friend and chief competitor, a young man named Castley, told Roberts:

“It’s no use your talking, old boy – you know Greek books better than I do: if I know two or three Greek books better than you do, it is just because I read them carefully at a good school and you did not. But you know Greek Testament far better than I do.”

Throughout his career Roberts’ exceptional grasp of the classical languages accelerated his ascent of the socio-economic ladder nearly as forcefully as his working-class roots impeded it. In 1859 Roberts applied to become an ordained deacon, for which he had to sit an examination. In the interview with Bishop Thomas Short of St. Asaph, his Oxford-educated examiner opened a page of Xenophon’s Cyropaedia at random and told him to translate, explaining: “When I want to know if candidates know any Greek,” said Short, “I always try them with Xenophon, it’s such Greek Greek.” Roberts had not read a line of the Cyropaedia:

“But I had happened to light on a plain passage and got through pretty creditably. “That will do” said Bishop Short. “You don’t seem quite to see the force of it, but never mind – let’s try the Greek Testament.”