Description

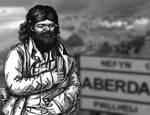

All rise for the ragged Rev. George Martin (1864-1946), alias ‘Saint George of Southwark’, who gave up his priestly salary (£700 p.a.) as a Cornish clergyman to work as a porter in Borough Market and attend to the spiritual and material needs of the working poor in Southwark, London.

All rise for the ragged Rev. George Martin (1864-1946), alias ‘Saint George of Southwark’, who gave up his priestly salary (£700 p.a.) as a Cornish clergyman to work as a porter in Borough Market and attend to the spiritual and material needs of the working poor in Southwark, London.

In an illuminating and by no means effusive character portrait entitled ‘Meet the Priest Without a Parish’, Guy Aldred recalls: “He moved about a tough neighbourhood fearlessly, but was very gentle with all who erred and suffered. Every day he… would leave the market to take a troop of eighteen down-and-outs across to Lockharts’s Tea Rooms for tea or cocoa, bread-and-butter. He gave away all he earned and most of his allowance from home. When not ministering to the people, he divided his life between the most severe introspection and classical studies… He loved scholarship and his society was a joy, for its quaintness, his classical digressions, and his broad human understanding… His love of Greek, and his interest in teaching it, amazed me for I was his victim.”

We might assume that the anarchist and atheist Aldred was not the only ‘victim’ of Martin’s Hellenism. In his nearly fifty years at Southwark he surely had occasion to teach Greek and tell classical tales to many more appreciative students. Martin, at times referred to as the ‘modern St Anthony’ – for his selfless generosity, was born into a wealthy Cornish family and received a traditional classical education at Blundell’s School near Tiverton, in East Devon. It was at Blundell’s that Martin gained his facility in Latin and Greek, but his classical reading widened and deepened at St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he read for Holy Orders and admission into the Anglican clergy.

Among generations of Southwark residents it was widely known that if anyone fell on hard times they could always turn to the strange bearded priest for help. When a child in his community was taken ill, for example, and required 24-hour care, Martin alternated with the father keeping watch through the nights until the boy recovered (see picture – Milwaukee Sentinel January 1948). When a fellow worker was disabled, Martin divided his earnings with the man’s family until he could once more return to work. Kind, gentle and outstandingly generous he certainly was to the poor of Southwark, but his anti-capitalist activism sometimes landed him in serious scrapes with the law.

Among generations of Southwark residents it was widely known that if anyone fell on hard times they could always turn to the strange bearded priest for help. When a child in his community was taken ill, for example, and required 24-hour care, Martin alternated with the father keeping watch through the nights until the boy recovered (see picture – Milwaukee Sentinel January 1948). When a fellow worker was disabled, Martin divided his earnings with the man’s family until he could once more return to work. Kind, gentle and outstandingly generous he certainly was to the poor of Southwark, but his anti-capitalist activism sometimes landed him in serious scrapes with the law.

Dressed in a ragged frock-coat and old workman’s boots, and nourished on bread and margarine alone – Martin was enraged by what he considered to be the misspending of public money in his borough. For example, in 1902 he was apprehended in the grounds of Buckingham Palace, attempting to hand deliver a letter of protest to the King about the extravagance of the proposed celebrations of the coronation of Edward VII. Spectators’ stands were to be erected from which vantage point the local nobility could watch the royal procession as it passed. Martin saw these stands, in his own words, as representing “the league between the Church and the more affluent classes, which is at present so great a barrier to a large proportion of the people”.

On realising that his protestations had fallen on deaf ears he threatened—and afterwards actually attempted—to blow up the stands with gunpowder. On the day of the coronation Martin was picked up by the police approaching the stands in possession of his homemade bomb. He intended, again in his own words, ‘to strike a blow for Christ’.