Description

Admire the heart and conviction of Tisa Schulenburg, who–after being born into Prussian nobility and raised among the upper echelons of Nazi Germany–emigrated to England in the 1930s and dedicated her life to cultural work in the most socially deprived regions of England.

Admire the heart and conviction of Tisa Schulenburg, who–after being born into Prussian nobility and raised among the upper echelons of Nazi Germany–emigrated to England in the 1930s and dedicated her life to cultural work in the most socially deprived regions of England.

After her younger brother Wilhelm died in 1936, she later recalled, ‘it seemed impossible to me to go on living in the same way. I decided to change my life. By change I meant dedicating myself to an idea. Not just living for myself. I wanted to get out of the ivory tower.’

While in East Anglia that year she joined the antifascist AIA (Artists’ International Association), which brought her into contact with such artists as Duncan Grant, Mischa Black, Stephen Bone, Julian Trevelyan, Vanessa and Clive Bell, Henry Moore, Nicolson and Barbara Hepworth. She was quickly elected to the Association’s committee.

‘Everyone was left-wing’, she explained, ‘without belonging to any political party’. In a typewritten autobiographical essay among some papers now held by Newcastle University’s Special Collections, she candidly discusses the nagging questions that haunted her mind in that pivotal period of her life:

‘Did I know England? I only knew the upper middle class. I wanted to know the other rungs of the social ladder, be less narrow. The worker was the hero of my dreams. What was he like? How did he live? I was soon to know.’

Later in 1936 she was invited to the Durham County coalfield to speak on art in the workingmen’s clubs and give some woodcarving demonstrations. Tisa Hess (as she was at that time) ended up settling in the area for a couple of years and contributing towards the incredible creative outpouring of the Spennymoor settlement, as well as promoting the artwork of miners, employed and unemployed alike, in the Northeastern coalfield.

Later in 1936 she was invited to the Durham County coalfield to speak on art in the workingmen’s clubs and give some woodcarving demonstrations. Tisa Hess (as she was at that time) ended up settling in the area for a couple of years and contributing towards the incredible creative outpouring of the Spennymoor settlement, as well as promoting the artwork of miners, employed and unemployed alike, in the Northeastern coalfield.

One settlement member, Arnold Hadwin (who became a respected newspaper editor and recipient of an OBE), recalled Tisa telling him that she remembered that first day: ‘standing in front of thirty men in caps and mufflers, faces thin and emaciated. I was struck dumb. But I stayed on to teach them how to carve. It was in Spennymoor that the door to England slowly opened. I had found a community I could serve; a cause that inspired me.’

In her journal Tisa called the settlement a ‘pit university’ where ‘volunteers helped by teaching art and drama and giving lectures’. The art produced by the workers with whom she worked grew out of their immediate surroundings and experiences. Everyone in the mining communities were, Tisa observed, completely obsessed with the pit. It is hard to find evidence for significant influence from Greek and Roman antiquity on their work. This is most likely because there was little. The settlement was chiefly concerned with promoting working-class culture, i.e. homegrown drama and art based on lived experience. As such, classical culture was ostensibly beyond their primary remit. Members naturally painted, sketched and sculpted that which they saw and told stories about that which they knew. Through the many and diverse classes held in the ‘pit university’–including those tutored by Tisa, who had been educated at the Berlin Academy of Art in the 1920s–some members explored in depth their favoured crafts and academic subjects in increasing detail, which inevitably led them in their reading back to the classical world, and the origins of Western art and culture (see for example Plato Settles in Spennymoor).

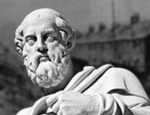

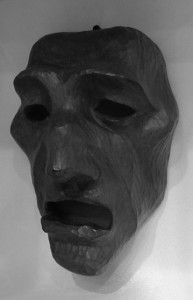

Tisa Schulenburg made an indelible mark on the lives of many of the settlement’s members, and left an important physical legacy too carved into the settlement itself. Above the entrance of the Everyman Theatre proudly stands a replica of Tisa’s original sandstone frieze, which was moved indoors in 2000. The frieze shows two workers holding the ancient Greek masks of tragedy and comedy, which were themselves likenesses of Spennymoor locals carved by the German artist.