Description

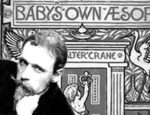

Marvel at the minute masterpieces of Thomas Bewick the innovative wood-engraver, famed for his lively illustration of birds and beasts. He was one of eight children of a tenant farmer and small-time colliery manager. Despite limited formal education at local schools, Bewick enjoyed a close relationship with Aesop’s Fables from an early age. In the family home he was fortunate enough to have a few books with which he could practice his reading. His favourite book by far was Croxall‘s 1722 edition of Aesop’s Fables, which were especially attractive to the future artist for the beautiful illustrations by the 18th-century printmaker Elisha Kirkall.

Marvel at the minute masterpieces of Thomas Bewick the innovative wood-engraver, famed for his lively illustration of birds and beasts. He was one of eight children of a tenant farmer and small-time colliery manager. Despite limited formal education at local schools, Bewick enjoyed a close relationship with Aesop’s Fables from an early age. In the family home he was fortunate enough to have a few books with which he could practice his reading. His favourite book by far was Croxall‘s 1722 edition of Aesop’s Fables, which were especially attractive to the future artist for the beautiful illustrations by the 18th-century printmaker Elisha Kirkall.

When Bewick reflected on his schooldays, it was predominantly of corporal punishment that he wrote. He played truant from his first school in Mickley following an episode in which he resisted a thrashing from his teacher. Things did not improve much when he moved to the larger school in Ovington, presided over by the cane-loving Revd Gregson. But it was under Gregson that Bewick learned the little Latin that he did. In his autobiography the artist reveals himself as an unenthusiastic scholar:

“I was put to learn Latin but, as I never knew for what purpose I had to learn it, the margins of my books and every spare and blank paper became filled with devices and scenes I had met with and with wretched rhymes explanatory of them. As soon as I filled the blank spaces in my books I had recourse to the gravestones and floor of the church porch, with a bit of chalk.”

From his teens, however, he mixed with various groups of Newcastle radicals, including Thomas Spence, the notorious author of The Real Rights of Man. Inspired by the vigorous debate of such literary friends, Bewick developed a keen interest in learning and–although funds were tight–in 1770 bought himself a 17th-century edition of Phaedrus (who wrote versions of Aesop in Latin).

From his teens, however, he mixed with various groups of Newcastle radicals, including Thomas Spence, the notorious author of The Real Rights of Man. Inspired by the vigorous debate of such literary friends, Bewick developed a keen interest in learning and–although funds were tight–in 1770 bought himself a 17th-century edition of Phaedrus (who wrote versions of Aesop in Latin).

There are traces of Bewick’s radical tendencies to be found in his engravings. For example, in the intricate tail-piece (main image above) from the General History of Quadrupeds (1790), the crack in the wall surrounding the lush woodland hints towards the perceived fragility of land enclosure, against which radicals such as Spence railed. The sign above the crack reads “steel traps and gins”, serving to deter trespassers as well as indicate (like the bird house) the bloody desire to obliterate freedom. The classical bust and urn stand as symbols of opulence and governance, in stark contrast with the ragged dress of the beggar boy, who leads two blind fiddlers on their footloose course.

There is a rich tradition of political interpretations of Aesop’s Fables by the British and, later, American radical left. An early example of this tradition is found in Brooke Boothby‘s Romantic-era translation, which inspired Bewick to begin his final major engraving project in 1812. Throughout his working life Bewick returned to Aesop. His first engagement with the Greek fabulist came during his apprenticeship to the Newcastle bookseller Thomas Saint. In 1775 he illustrated a version of Aesop by the writer and publisher Robert Dodsley (published 1776), adapting the designs from Kirkall’s 1722 Aesop. From 1812 to 1818 and in collaboration with his brother and multiple apprentices, he illustrated Boothby’s Aesop (1809), which included 165 fables. In late 1814 he wrote of how much he was enjoying his return to Aesop: ‘I think I pursue it with an ardour & enthusiasm that borders upon being crazey [sic] .’

n.b. around 1770