Description

Meet the famous French classical translator Madame Dacier (1645-1720), who picked up the basics of Greek and Latin, while bent over her needlework in the same room where her father–the brilliant autodidact scholar, Tanneguy Le Fèvre–was teaching her brother. When Anne began to show more promise than her brother, Tanneguy turned his attention to her too. In a letter to a friend (lurching between French and Latin), Anne’s father once described her as “de belle taille: multum dignitatis habet. In animo autem nihil humile, nil demissum, nil plebeium” (“[she has] a pretty shape: is most dignified. In her spirit/mind, however, she is not at all humble, nor shy, and by no means vulgar”).

Meet the famous French classical translator Madame Dacier (1645-1720), who picked up the basics of Greek and Latin, while bent over her needlework in the same room where her father–the brilliant autodidact scholar, Tanneguy Le Fèvre–was teaching her brother. When Anne began to show more promise than her brother, Tanneguy turned his attention to her too. In a letter to a friend (lurching between French and Latin), Anne’s father once described her as “de belle taille: multum dignitatis habet. In animo autem nihil humile, nil demissum, nil plebeium” (“[she has] a pretty shape: is most dignified. In her spirit/mind, however, she is not at all humble, nor shy, and by no means vulgar”).

The family’s financial situation was always precarious thanks to Le Fèvre’s refusal to give up his Protestant faith (which severely limited his opportunities at Court). After her father’s unexpected death in 1672, Anne went to Paris. Before his death Tanneguy had imagined that Anne might make a good governess… but she had other plans.

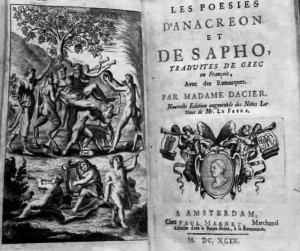

After producing some commissioned editions of classical authors for the series ‘ad usum Delphini’ (for the use of the royal prince) and an edition of Callimachus, she turned her attention to producing vernacular (French) translations (with explanatory notes) of: Sappho and Anacreon (1675 – main image above), Plautus – selected plays (1683), Aristophanes – selected plays (1684), Terence – selected plays (1688), and Homer’s Iliad (1711) and Odyssey (1716). These translations were designed to make Greek and Roman authors accessible to those who did not know the learned languages–after all is was (supposedly) only wealthy men who were trained in those days to read Latin, let alone Greek.

After producing some commissioned editions of classical authors for the series ‘ad usum Delphini’ (for the use of the royal prince) and an edition of Callimachus, she turned her attention to producing vernacular (French) translations (with explanatory notes) of: Sappho and Anacreon (1675 – main image above), Plautus – selected plays (1683), Aristophanes – selected plays (1684), Terence – selected plays (1688), and Homer’s Iliad (1711) and Odyssey (1716). These translations were designed to make Greek and Roman authors accessible to those who did not know the learned languages–after all is was (supposedly) only wealthy men who were trained in those days to read Latin, let alone Greek.

Of Madame Dacier’s classical translations the most important were her Aristophanes’ Clouds and Plutus because their publication signalled the first ever time that a complete play of Aristophanes had been produced in French. It was also deeply daring because his comedies were far too racy and low-brow for contemporary French tastes.

According to the court historian Saint-Simon, the extraordinarily learned Madame Dacier could, when she wanted, pass for an ordinary witty woman in the literary salons of the time, and even make small talk about hairstyles and fashion as though she were capable of little else!

n.b. around 1680

encounter by Dr Rosie Wyles