Description

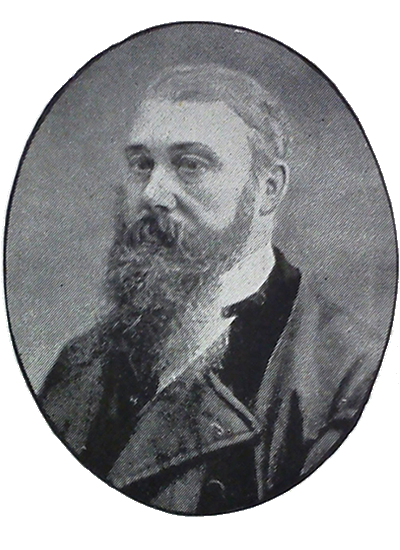

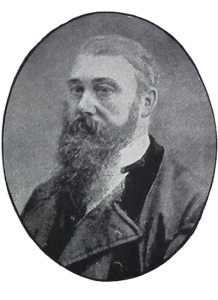

Meet John Askham (1825-94), shoemaker poet and Roman Britain enthusiast, who proudly put bread-winning labour before his literary pursuits.

Meet John Askham (1825-94), shoemaker poet and Roman Britain enthusiast, who proudly put bread-winning labour before his literary pursuits.

Askham took up poetry when he was 25 and published four books in his lifetime. Each was funded by subscription, winning pledges from local nobility and his fellow workers alike. His writing often refers to the kinds of culture we might imagine to have been beyond the reach of an uneducated working man.

In a poem called Irenia, about a newly discovered Roman fort at Irchester, Askham tells of how the ancient Britons fought against the Roman invaders, proudly invoking: ‘Caractacus the valiant’ and ‘Boadicea the queenly’ [*shudder*].

The poem bounces whimsically on to the present day (c. 1890), when:

Came a fresh invasion

Of shovel, pick, and spade;

And the secret of the centuries

To the gaze was open laid.

And the Roman fort and city

That stood beside the Nene,

In the time of puissant emperors,

Sees the light of day again.

Shelley he may not be, but Askham here effectively captures the excitement surrounding the 19th-century excavation of Roman Britain. Archaeology was popular not only among aristocratic antiquaries, but working-class men and women too came face to face with classical culture when they dug up ancient objects in and around their own back yards. Small museums sprang up all over Britain displaying local finds and curiosities.

The classical world conjured by Roman British archaeology was not the one of epic poetry or history books, but rather a world in which (as Askham stresses) people crafted “fair-shaped water-pots” and millstones were “into deep hollows worn;” where “instruments of toil” were more plentiful than “weapons of warfare.”

In a lively review of a tour around Buxton for his local paper Askham describes a visit he made with “a score of common mortals” to Chatsworth House. Here he saw:

“Marble statues by the great masters themselves, Canova, Thorwaldsen, Rinaldi, Gibson, and a host of others famous for their chiselling propensities. Figures colossal, busts of great men, huge lions, tigers, and dogs that seem to breathe; groups that must have been the work of years, vases of rare beauty, one especially, the bowl of one block of granite; Venuses, Cupids, Sleeping Beauties, Hebes, Mars, and all the rest of them.”

Who would have thought “a score of common mortals” in 19th-century Yorkshire would have been within reach of the great classical sculptures, imported directly from the continent? Such artwork was otherwise open only to the extremely wealthy, who could afford the exorbitant expenses of life on the Grand Tour. Askham brings his artistic flight of classical fancy back to earth with a grouchy bump when he concludes: “We could wish the floor less slippery, as we hobble from one room to another.”

n.b. around 1890